Pakistan History

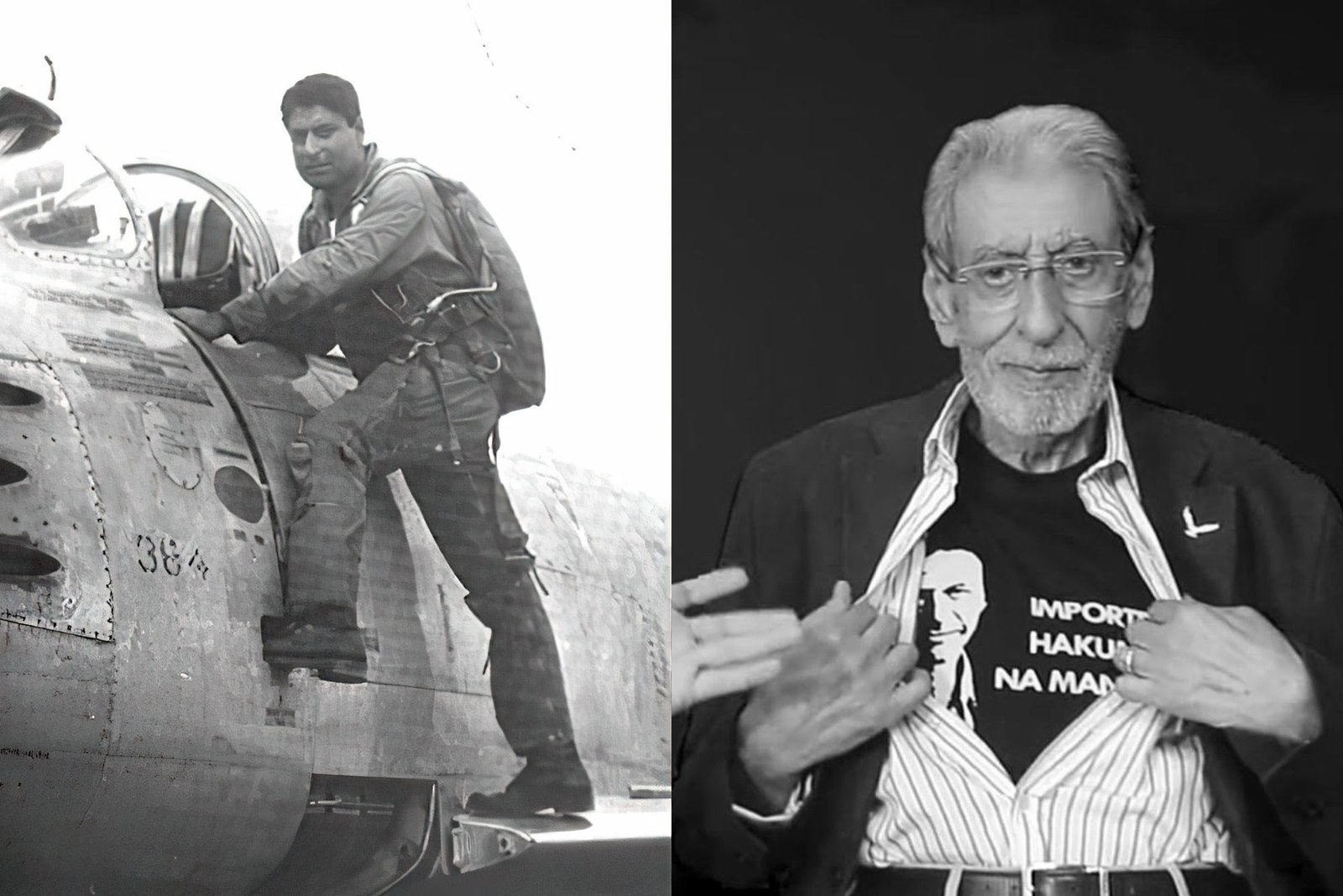

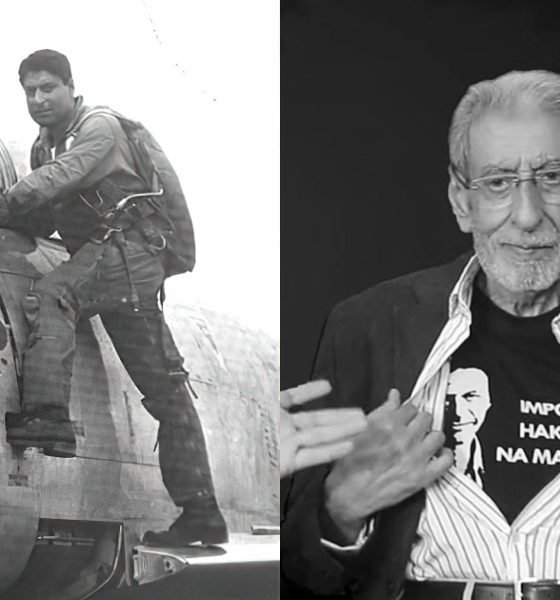

Air Commodore (retd.) Syed Sajad Haider: The Saviour of Lahore and Pakistan

Air Commodore (retd.) Syed Sajad Haider lead the Sherdil Squadron that destroyed the Indian tanks about to enter Lahore on 6 Sept. 1965. Today, he is still defending Pakistan.

“…Oh hang on a second, you’re being a little bit modest now. You are one of the heroes of [the] ‘65 war, and you’re being very modest about it. You must have done something that puts your name in history.”

“Well, I always say one thing. Nothing worthwhile in life is achieved by a single person. Whatever reputation that has been accorded to me, or the accolades that have been given to me, are in fact deserved by those who flew on my wings. So that whole team created the situation on the ground, [the] destruction of the enemy. It wasn’t single me. I just led them there, that was my job. That was something that I had been trained for all my life. And I had trained them to make sure that when they shoot at the target, they destroyed [it], and that is what they [did]. So it was teamwork.

You’re alluding to the book concerned, nowhere have I used [the words] “I did this” or “I did that.” I have used “we have done that.” I was leading a team and I was, by the grace of God, successful because I had trained this team in 65 and 71. I trained them to fight every single day of their life and they were war-ready like nobody, their war readiness was unmatched. That is [why] they performed.”

These words of Air Commodore (retd.) Syed Sajad Haider, Sitara-i-Juraat, aptly describes why the 19th Squadron under his command made history. But before we delve deeper into the stories of the “saviour of Lahore,” here’s a brief introduction of Syed Sajjad Haider.

Syed Sajad Haider was born in Sargodha to noble parents: Sayed Fazal Shah, a respected doctor, and Rashida Begum, a full-time mother and disciplinarian. His mother found time to do quite a bit of social work for the poor, especially tuberculosis patients.

He grew up in Quetta, amidst the fierce tribal culture of the Baloch and Pashtoons, such as the Bugtis, Marris, Kansis, Jogezais, and Durranis. Like any young, growing boy, Sajad Haider had a dream: to grow up and make his parents’ lives comfortable after the World War II depression, which caused a scarcity of essential products and life necessities.

Sajad Haider’s family lived off ration cards, with which they were able to get sugar, flour, tea, eggs, cooking oil, petrol, etc. He mentions that he “didn’t really feel the cold drift of war, as mother made many sacrifices to keep us warm and well-fed.”

Once the world war catastrophe was behind, Sajad’s dream started taking shape. This dream found an expression when he first saw Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the Quaid-e-Azam, his idol, as he sat in awe of him only 6 feet away at his old school in Quetta. That is when the seed of becoming the defender of the nation became his obsession.

Sajad Haider details this further: “The very next day I saw three Spitfires (WW-II fighter aircraft) overhead conducting a mock dogfight. Now my dream had reached the sky, and I wanted nothing else in life but to become a pilot. The problem was that my father wanted me to become an engineer, which was somewhat utopian considering my mediocre performance in school. The other was a serious emotional issue with my mother, who absolutely refused to let me go for a perilous profession like flying. For her, that was like courting death and disaster. It was a long, hard battle till she let me go, not willingly but surely tearfully.”

Sajad Haider describes himself as a mischievous kid between the ages of 14 and 18, which was a constant worry for his “anxious mother.”. “I would try every trick, game, and ruse, testing my endurance to the limit. That meant many small injuries and parental retribution, which came swiftly and was, at times, brutal. I didn’t cower down after the searing pain from the punishments. Ostensibly, I had a nature and personality that sought constant challenge, fully cognizant of the consequences if caught.”

Sajad Haider was selected to join the 13th General Duties Pilot Course at the Royal Pakistan Academy. The prefix ‘Royal’ denoted Pakistan’s dominion status as a former colony. Haider recalls himself as an “average student who scraped through the course of one and a half years.” But within months after getting his pilot’s wings, he “blossomed to the top of [his] course, where [he] had barely made the middle during the training period.”

After he was posted to No. 14 Squadron, Haider discovered that his flying talent was not short-lived and confined to the Fighter Conversion School, where he catapulted to the top.

Soon, Haider was posted to the first jet squadron of the RPAF. “This was a great honour, to fly the “Supermarine Attacker,” a euphemism for a flying coffin, which proved a great asset when the PAF switched to the USAF Saber jet.”

Sajad Haider: The Saviour of Lahore

The Dawn of September 6, 1965, saw a formation of six F-86s of No. 19 Squadron fully loaded with 5-inch rockets (a last-minute premonition the night before by Air Marshal Nur Khan, the Commander in Chief, which paid rich dividends) flying on “Hot Patrol’. The moment the Air Defense Commander learned of the Indian Army’s advance towards Lahore, the 19th Squadron formation was diverted to stop the advancing Indian armour columns at Wagah. The No. 19 Squadron was led by none other than Syed Sajjad Haider.

In twenty minutes of action, the Grand Trunk Road was littered with scores of burning tanks, armoured and soft vehicles. The 5-inch rockets had devastated the enemy armour. The formation led by squadron leader Sajad Haider with flight lieutenants M. Akbar, Dilawar Hussain, Ghani Akbar, and flying officers Khalid Latif, and Arshad Chaudhry brought the Indian attack to a dead halt.

Here is Sajad Haider’s account of what transpired that morning:

“After the air battle over Kashmir, where the Indian Air Force lost five fighters, the next air action of the 1965 war came on September 6, at 0930. It was the first mission of war assigned to No. 19 Sherdil Squadron, which I had the honour to command. The target assigned was an enemy artillery regiment across the Jassar Bridge in the Sialkot-Shakargarh bulge.

The squadron had been trained to be second-to-none. Each pilot wore this dedication to excellence on his sleeve and understood well that excellence was not an option but an instinct for mission accomplishment. Five minutes away from the target area, the radio crackled, and the voice of our Air Defence Commander was discernible. He instructed us that our primary mission [was] cancelled and that we were to proceed to the village Attari and destroy enemy forces about to enter Lahore. He may as well have transmitted a million-watt electric shock to us with the word ‘Lahore’.

But we were taught never to react to any situation with anger, so we took it in stride [and proceeded] to head for this village, although I had no idea where it was. I was told to head for the Wagah border, which is the border between Pakistan & India. We flew very close [to the ground] and people thought that there some bombs had dropped or somebody had gone through the sound barrier. That’s how the Lahoris reacted to the noise of six aircraft going down that level. We went up to Amritsar, [since] we couldn’t find anything. Another aircraft from Sargodha had been there [too] but he had not found the Indian Army on the ground. We went all the way to Amritsar, and I saw the whole sky was full of shells and smoke. When we arrived at the target, I saw tank tracks and as I followed the tracks, I saw them climbing up near the BRB canal, which is the last defence of Lahore. I thought those tanks that I saw were Pakistan army’s tanks. So my first transmission was “alright boys, thank God the Pakistan Army is out, I can see the tanks now coming but let’s give them a salute.” So I put my aircraft on its back and flew over this tank, very low, about 30-40 feet over him, and I saw a roundel which hit me in the face. That was an Indian saffron roundel of an Indian tank, and what I was taking for [the tanks] being Pakistani were actually Indian. The expletives that I used are not fit for [this article]. I pulled up and I fired my first two rockets. Now when you fire rockets, you don’t wait to see them, otherwise, you’ll also go into the ground. So when you fire rockets you immediately pull up very steeply, and we’re firing these 5-inch rockets which were not something we had been fighting or used to. So I worked out a different kind of profile, for that we had to pull up very swiftly and very steeply to avoid shrapnels from the target. These tanks were full of ammunition and full of fuel and oil, so when the rockets hit them, [they] blew up. We were there for 17 minutes, which is a record in history. You will find that no formation stays more than one or two attacks on the ground track, but [we] made history. Even Indian historians, especially three journals, have marked that this formation stayed for 16 to 17 minutes over the target and devastated the entire frontal attack. We destroyed, we thought, 11 aircraft at that time. The Indians have now, in 2010, 2012, and 2015, confirmed that 13 aircraft were destroyed in that attack.”

What happened is best described in an account of PAF’s air action at Wagah by Gen. Lachhman Singh, Gen Sukhwant Singh and award-winning historians Jagan Mohan and Samir Chopra, quoted here in parts:

“No.19 Squadron from Peshawar, led by Syed Sajad Haider, flew a six aircraft strike mission at 0930 hours against the leading elements of Indian army thrust towards Lahore. The leading battalion of the division, 3 Jat, led by Col. Desmond Hyde had its columns strafed and rocketed by PAF sabres. The unit lost all its Guns and Sherman Tanks … (Lachhman) …. It was about 9.30 am and the enemy aircraft shot up every vehicle for about 15 minutes undeterred by fire from our troops.”

Syed Sajad Haider: The Pathankot Airstrike

Later in the day, at 1200 hrs., Sajjad Haider and his team got another mission which “is the dream of any commander.” It was to strike the Indian Air Force (IAF) at their base of Pathankot, and this is the famous strike that they carried out. This was their third mission of the day.

After landing at Sargodha for refuelling, the formation rushed back to Peshawar to prepare for the strike on Pathankot. Having rested a while, the pilots were assembled for a final briefing at 1600 hrs. After a briefing and after going over the already well-rehearsed strike plan, squadron leader Sajad Haider surprised his pilots by asking for a bucket filled with fresh water. He pulled out a bottle of No. 4711 Eau-de-Cologne from his coverall pocket and emptied it into the bucket. He took small white towels, dipped them in the water, and after wringing them out, handed over one each to his pilots. “This could be a one-way mission, and if we meet our Maker, we should be smelling nice,” Sajad Haider remarked.

Everything proceeded according to plan, and the formation got airborne at 1630 hours, climbed in battle formation up to about 11,000 metres and then dived down to tree top level and set course for the initial point (IP) for the target.

The planning staff was not certain whether Pathankot would still be occupied by IAF aircraft after the outbreak of hostilities. But the formation of eight Sabres, escorted by two more sidewinders equipped with F-86s acting as top cover at 6,000 metres was fortunate.

A glimpse of the other side of the story is also presented from the website Bharat Rakhshak:

“Meanwhile, at the IAF Air Base at Pathankot, the station commander, group captain Roshan Suri had just returned from a meeting of station commanders from Western Air Command. Suri briefed his squadron commanders on the impending army move to cross the international border. As evening approached, Pathankot Airbase received an urgent phone call from squadron leader Dandapani at Amritsar Air Defence Centre. He spoke to wing commander Kuriyan and informed him that several Sabres had been observed taking off and then going ‘off the scope’ as they all went below the radar horizon. This had all the tell-tale signs of an incoming raid. Kuriyan informed Suri about the suspicions of a raid and asked for permission to scramble the CAP (Combat Air Patrol). Suri refused to order the CAP to go off and ordered Kuriyan to go off the shift.”

The PAF aircraft reached Pathankot precisely on time at 1705 hours and discovered a large number of IAF aircraft parked around in protected dispersal pens. With no enemy fighters in the vicinity and fairly thin ground fire, ‘Nosey’ set the ball rolling with four carefully positioned dives from about 500 metres, systematically selecting individual aircraft in protected pens on the airfield for his fixed-gun attacks. He was gratified to recognize the distinctive delta-winged MiG-21s- India’s latest fighter – among the aircraft on the ground and singled them out for special attention.

The rest of the pilots followed suit. Each pilot had been briefed to make only two passes but the lucrative targets and limited opposition enabled them to make multiple passes. Wing Commander Tawab, flying top cover, counted at least 14 fires burning on the airfield.

“Wing Commander Kuriyan was just then driving into his garage at his house when he heard the ack-ack guns booming. He looked towards the airfield to see four F-86 Sabres bore down the airfield at a low level firing their machine guns, while two F-104 Starfighters kept a high altitude as covers. As the four Sabres pulled out, another four bore in. The Sabres strafed buildings, installations and aircraft on the ground.

Some Mysteres on the ground bore the brunt of the raid and were damaged, as were the two MiG-21s. Only the fact that the Sabre’s 0.50-inch machine guns could fire ball ammunition instead of exploding cannon shells prevented further damage. The Sabres slipped off unscathed as even the airfield defences were caught napping.

For the PAF this raid was a cakewalk. All in all one C-119, four Mysteres, two Gnats and two MiG-21s were destroyed in this highly successful raid by Pakistan Air Force.

IAF admits to the loss of only two MiG-21s but it goes to the credit of PAF that after the fateful strike on Pathankot, Indian MiG-21s were not seen in the air for the remaining duration of the 1965 War.

Sajad Haider’s Legacy

Air Commodore Sajad Haider‘s impact on the Air Force wasn’t limited to the Indo-Pak War of 1965. The generation of air pilots that he trained and raised climbed to the very top of Pakistan’s Air Force. Of his squadron, five became Air Marshals, two became Air Chief Marshals and 6 became Air Vice-Marshals. As for Sajad Haider, he retired as an Air Commodore, not because he wasn’t good enough but because there was another problem. Sajad Haider describes it in the following words:

“I left the Air Force because I stood up to a dictator, Zia Ul Haq. In a meeting where he was to announce that he had decided to postpone elections indefinitely, I was the only person who stood up and said, “Sir I give you a dissenting note on that.” I gave him a riposte, a very strong one! I said the heart of this nation is not beating for Pakistan but from the fear of the whip. The Islam that he had brought divided society. So I stood up and told him that I did not agree with his decision to postpone elections and that the intelligence agencies were not informing him about the state of the nation. And that nation was in a terrible state, [and] was being treated like animals. It was because of that that I left the Air Force and I’m very proud of having done that. Now if there is any sense of, I wouldn’t call it heroism, but pride in me, it is because I stood up to a dictator myself.”

Air Commodore Sajad Haider fought and defended Pakistan when the country was on the brink of an invasion. He stood up to a dictator, and today, at the age of 91, Syed Sajad Haider is still fighting for Pakistan. This time, for Pakistan’s Haqiqi Azadi. He may not have the same strength in his arms or legs, but his conviction and determination for the cause of Pakistan are still the same. In any case, the squadron leader & Sitara-i-Juraat, Syed Sajjad Haider, is etched into Pakistan’s history for the times to come.