Pakistan History

Did the U.S. Enable Pakistan’s First Military Dictatorship?

In 1953, Ayub Khan assured the U.S. that the Pakistani army would safeguard American interests during the Cold War.

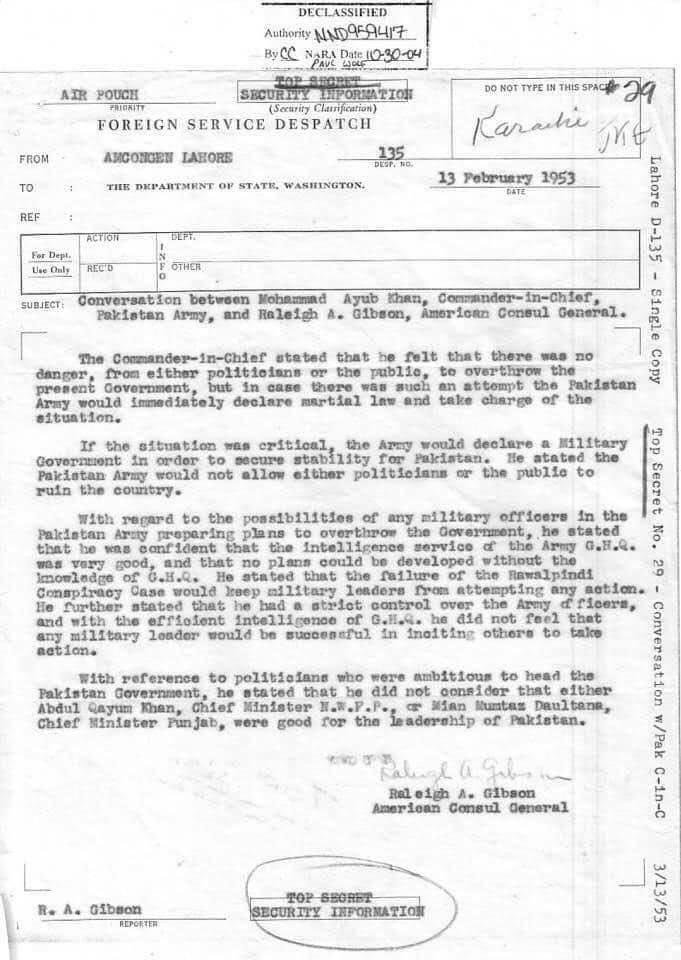

In 1953, the then Commander-in-Chief—and spiritual forefather of the Pakistani military—Field Marshal Ayub Khan, reassured American Consul General Raleigh A. Gibson that “the Pakistan Army would not allow either the politicians or the public to ruin the country,” and “if the situation [were] critical, the Army would declare a military government to secure the stability for Pakistan.”

He further stated that “he felt that there was no danger from either [the] politicians or the public, to overthrow the present Pakistani government, but in case there was such an attempt, the Pakistan Army would immediately declare martial law and take charge of the situation.”

At the time, Khawaja Nazimuddin—Pakistan’s second Prime Minister—was in office. Two months later, he was replaced by Muhammad Ali Bogra as the third Prime Minister, who stayed till August 1955.

Between 1956 and 1958, Pakistan cycled through multiple prime ministers. It was during this turbulent time that Ayub Khan found a convenient pretext for political instability, which he used to orchestrate the 1958 Pakistani military coup, the first military coup in Pakistan that resulted in the toppling of Iskandar Ali Mirza, the President of Pakistan, by Field Marshall Ayub Khan, the commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army.

Interestingly, Ayub Khan in the same meeting had remarked on ‘the possibilities of any military officers in the Pakistan Army preparing plans to overthrow the Government, that he was confident that the intelligence service (ISI) of the Army G.H.Q. was very good, and that no plans could be developed without the knowledge of the G.H.Q.’

Keeping aside the political turmoil and its causes, the more pressing question is this: how was the military commander discussing the possibility of martial law and a military regime with the Americans?

The U.S. response to such a proposition is secondary; what matters more is Ayub Khan’s audacity, mindset, and remarks that are nothing but a reflection of the colonial hangover.

As stated earlier, Ayub Khan said, “The Pakistan Army would not allow either the politicians or the public to ruin the country.”

But let’s be clear: the “ruin” he referred to had nothing to do with the national interest of the Pakistani people. It was, quite plainly, a pledge to protect and safeguard American interests during the Cold War.

Here, one must ask:

- Who assigned the guardianship of Pakistan to the Pakistani army?

- By what right did the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces discuss the prospect of a military government with a foreign power?

- Was this not a more humiliating form of the White Man’s Burden—where the colonizer may have physically withdrawn but left behind his “civilizing mission” in the hands of brown (khaki) sahibs?

This is the most degrading form of slavery, where the master no longer needs to remain physically present to rule over his subjects because he has successfully bred a class from among the ruled, whose instinct for servitude is so deeply entrenched that the master can trust their “conscience” and “sense of judgment.”

Here’s the irony: This very Field Marshal Ayub Khan later titled his memoir ‘Friends Not Masters’.

One final point: this mindset, this colonial hangover, is not a relic of the past. It is well and alive, even today. In present-day Pakistan, elections, public mandate, and the people’s hopes are treated as threats—painted as disorder and chaos.

Those who seek legitimacy through ballots are termed anarchists and troublemakers, while the protectors and upholders of the status quo, the self-proclaimed guardians of the state, declare—through their loyal mouthpieces in the media and elsewhere—that only they will decide what serves Pakistan’s interests.

In this equation, your vote, your voice, and your chosen representatives carry no weight.